|

20 years ago on May 24th, 2001, Mark Auricht came to rest on Mt Everest at 7900m after 30+ hours of climbing and descending above 8000m in his pursuit of a dream to reach the summit and what transpired as a relentless struggle back, reaching for the life and loved ones he so cherished many thousands of metres below. An account of this story is shared with this blog below but as I reflect on his life and passing I want to let go of the grief and celebrate his life.

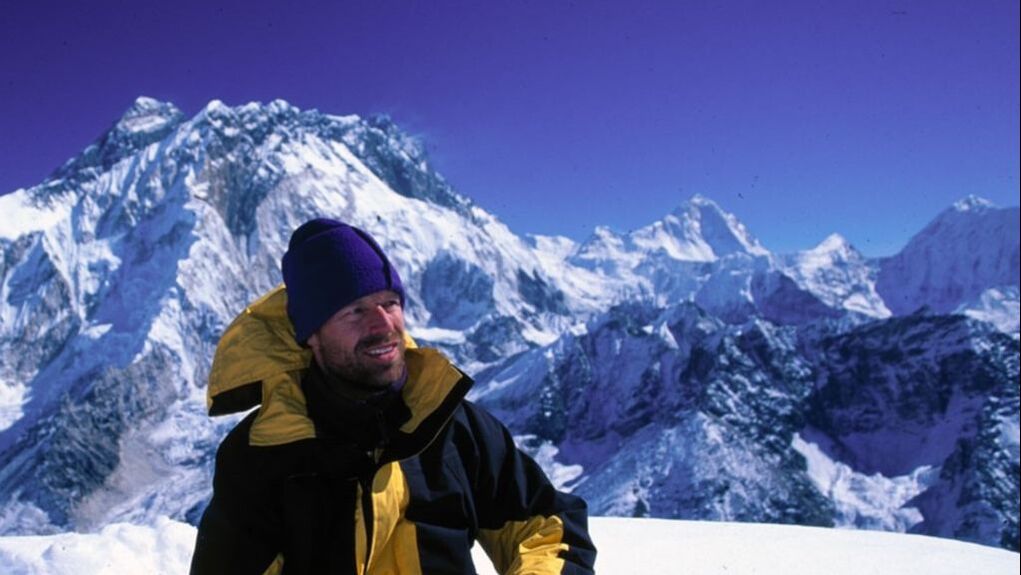

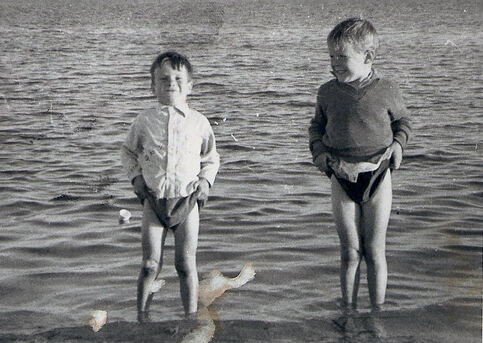

Show everyone my heart The light you encountered on the street You, my moon, are here with me Time to say goodbye Andrea Bocelli This post is an excerpt from the book: The Spirit of Adventure Calls: A Compass for Life, Learning & Leadership, which I wrote as a tribute to Mark and as a way of sharing his treasure. Chapter 5 Tributes to a Magnificent Human Being I remember Mark’s memorial service as if it were yesterday... As I sat in the Chapel of St Peter’s College, with hundreds of others who came to pay their respects and celebrate Mark’s extraordinary life, I saw an assortment of adventure gear and other symbols on the stage together with photographs of Mark that represented his essence. I sat in silence and looked at the ‘Order of Service’ booklet that I held in my hands. As I looked at his smiling face and read the words beneath it, my heart overflowed with gratitude for having known him and with grief for having lost this most precious friend. The words beneath his photograph said it all. Courageous Compassionate Inspiring Loving Strong Honest Caring Understanding Open Hearted Unassuming A number of people spoke at Mark’s memorial service, including friends, family, clients and expedition members. Mark’s brother Geoff spoke of Mark’s strength and fearless spirit Mark was capable, skilled, and strong in body and mind. He was an inspiration to all who knew him and many who didn’t. Mark would be humbled at the 100s of tributes which have poured in over the last few weeks and for the number and diversity of people who were here to honour and remember him today. We feel that Mark would not want us to mourn his death for too long but would wish us to celebrate his life and to remember the values he stood for. If he thought that in some way he had changed our lives for the better and inspired us to extend ourselves, rise to a challenge, or realise a dream, he would be delighted. David Tingay, the expedition doctor, represented the SA Everest Team In a lot of ways, I resent that mountain but I understand what it meant to Mark. He said that during the expedition Mark displayed a quiet confidence and a settling manner. These were exciting days for us. The freedom and sense of purpose was very apparent but there was always that sense of apprehension, and yet Mark would always come in smiling when he returned to Base Camp. He was never tired. Somehow he managed to show us the qualities we thought we didn’t have. He showed us the way things should be. Allan Keogh, represented corporate clients and colleagues Mark profoundly affected all those who came into contact with him. His lessons were simple, subtle and profound. Mark’s philosophy included ‘honouring the ordinary because that will encourage the extra-ordinary’ and ‘acting out of choice, rather than need or ego’, said Allan. During the week after Mark’s death numerous tributes were also reported in the local media. The tributes that follow are a few of many that emphasised Mark’s qualities of character over his achievements. Comments from Mark’s Family Mark rests in peace, embraced by the mountains that fascinated and challenged him... Mark was always true to, and cared for, his mates in life, and we all admired him for this... We congratulate Duncan and his Sherpas, who achieved their joint goal for which Mark had worked so hard. The Advertiser―May 26, 2001 Appreciation from a client group―A Tribute from ATSIC18 Mark, you encouraged us to look at our own fears and to face each challenge with courage and belief. You inspired so many people with your own courage, belief and vision so that we could succeed as individuals if we were prepared to believe in ourselves and have the determination to succeed. Courage is a special kind of knowledge. From this knowledge comes an inner strength that inspires us to do what seems impossible. Your courage and achievements are testimony to a man in pursuit of an inner vision with spiritual awareness. Your passion for life and the land, and your empathy with indigenous Australians made your work with us all the more meaningful. As a caring, understanding, passionate and sensitive man, you inspired us to stretch ourselves that little bit further. We cherish the moments we shared together. You shall remain an inspiration to us all. The Advertiser―June 1, 2001 Words from the Outdoor Education Association SA Following, are some of the words read out by Scott Polley at the OEASA Presentation Dinner on June 1, 2001 before presenting the inaugural Mark Auricht Award for Outstanding Achievement in Year 12 Outdoor Education. Mark’s contributions to the South Australian Outdoor Education and Recreation community were significant... but Mark was remarkable not only for his deeds but for the person that he was. He was an extraordinary person and yet an ordinary person also. He was a person of principle who listed among his associates those with little and those with substantial means. He always had time for you even when he didn’t have time for you. He was strong and yet vulnerable. Courageous and yet scared, pragmatic but deeply caring. He was passionate about fostering the development of others and has been a mentor to many outdoor education leaders in South Australia. Journal of the Outdoor Educators Association SA―August 2001 Alive Among the Mountains I once asked Mark what made him want to go back to the mountains of the Himalaya after the tragedy he experienced on Makalu. He had this to say:- It’s difficult to answer that question with much of a rational explanation, given the risks that are involved in climbing Everest. I love the mountains and the physical challenge involved in exploring my personal potential. I’ve always had a fascination with standing on top of the highest point on the globe. Perhaps because it represents the ultimate in what’s possible? Makalu gave me a heightened appreciation of life and a gratitude for being alive. I remember abseiling down from Camp 3 to Camp 2 after surviving the ordeal on Makalu and literally feeling the oxygen coming back into my body. I guess it makes no sense to those who would ask why I would risk my life again. As I stood on the ledge on my way back to safety on Makalu, I remember how beautiful the day was. I could see white puffy clouds below me; they looked so close that I could reach out and touch them. All I can say is I just love the mountains. They are one of the most beautiful places on earth and I feel so alive when I am amongst them. At the end of Mark’s memorial service his family played Andrea Bocelli’s ‘Time to Say Goodbye’ Whenever I hear it I remember him, as if he were sending a message across the mountains. Mostra a tutti il mio cuore Show everyone my heart La luce che, hai incontrato per strada The light you encountered on the street Tu mia luna tu sei qui con me You, my moon, are here with me Time to Say Goodbye Andrea Bocelli May Mark rest in peace in the arms of Chomolungma―Mother Goddess of the Universe.

0 Comments

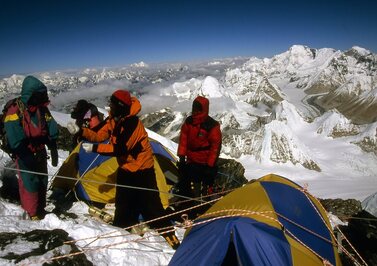

The above photo of the Everest Region was taken from the Rodungla Track in the remote east of the Bhutan Himalayas in 2018, while we traversed the country of Bhutan from west to east, then down through India. This is the closest I've ever allowed myself to get to Everest, as it both beckons me with its awe and sacredness, while also saddening me with the loss it represents for the families and friends of mountaineers such as Mark Auricht, David Hume and countless more. Everest itself is innocent and in someways its landscape and people are the victims of an unhealthy commercialisation of adventure and journeys into nature. I've been taking people on journeys into remote places for 15+years now and have always been mindful of the delicate balance between the benefits of adventurous journeys and the unhealthy impacts on the environment, local communities and, in the case of Everest and other extreme adventures, the toll on individuals and their family and friends when dreams turn to tragedy. It is now 20years since Mark Auricht's death on Mt Everest on May 24th, 2001. I was going to continue writing about Mark's journey on Everest after my last post (a year ago now) when I shared Mark's story about Mt Makalu and the death of his climbing partner and friend David Hume. I felt at the time that my posting of this story about how Mark died on Mt Everest might come across as gratuitous or inappropriate on the anniversary of his death, as it could be a painful memory for those who knew him. I still feel uneasy about this but my purpose for sharing an excerpt from the book I published in 2017 as a tribute to Mark, sharing some of the wisdom he imparted to myself and others, is to keep the spirit of his journey alive and to provide more insight into this tragedy and its impact. In the full version of this story, there is some commentary on the differing perspectives about the risks and rewards of mountain climbing and I explore some of the controversy around Everest, sometimes called the 'Dark Summit'. Aside from the 'dark side' of Everest, she is revered with great respect by the Tibetan's who call her Chomolungma - Mother Goddess of the Universe and by the Nepalese who call her Sagarmatha - Goddess of the Sky. It is the overly commercialised approach to some expeditions that cater for ego-driven 'summit-baggers', that have tarnished this sacred mountain and the people connected to this beautiful landscape and one could say that sometimes even those who have the most pure intentions of climbing respectfully have unfortunately become part of this tragedy which on the other side of the sword, can also be experienced as a triumph of the human spirit for those lucky enough to survive a summit attempt. Mark and I often philosophised about moral dilemmas and the pros and cons of climbing high mountains like Everest. I had the safety of pondering this subject while dabbling in lower risk adventures. He on the other hand tested his philosophy with his life. Whatever your opinions about risk-taking and the virtues or pitfalls of adventure, you might find this story enlightening among the tragic reality of risk taken to its extreme. Sometimes the edge between triumph and tragedy is so sharp and a hint of breeze can push us one way or the other. Understanding Leads to Healing Readers are often poorly served when an author writes as an act of catharsis, but I hope something will be gained by spilling my soul in the calamity’s immediate aftermath. John Krakauer―Author of Into Thin Air and Into the Wild In my personal experiences with grief and loss, it eases the heart and mind when we have more understanding about an event that disturbs us. With this in mind, I hope to shed some more light on what happened to Mark and perhaps, in the process, provide some catharsis for myself and others. I start this story by sharing the last two diary entries from the 2001 South Australian Everest Expedition. Everest ABC, Tuesday May 15 We returned to a snowy Advance Base Camp last night (14th May) after aborting our first summit push due to heavy snow falls. We reached a high point of 7600m but with high cloud rapidly approaching the decision was made to turn around. With both of us in good health and well acclimatised, it was a difficult but good decision. The ensuing snow fall and cloud has blanketed the mountain for the last 24 hours with no sign of improvement. All other teams have returned to ABC as the forecast predicts a further five days of snow falls and poor visibility. On the 14th of May a large and very experienced American expedition failed to reach the summit ridge due to deep snow and dangerous avalanche conditions, from their high camp at 8300m. This would have been the first expedition to have reached the summit from Tibet this year. The route above high camp has not been established yet so a strong large team will be required to force its way through the deep snow and fix the necessary rope. The general consensus in ABC is that if anyone summits this season, it will be late May. A couple of expeditions have self-destructed and have packed up and left already. Most other expeditions plan on waiting out the weather until the end of May and into early June. We hope to mount a second summit bid in a few days time. Everest ABC, Saturday May 19 Our latest plan is to leave tomorrow morning at 6.00am for our second summit push. The weather forecast has been totally wrong today and instead of 40-50 knot winds with heavy snow falls as we have had for the last week, the day dawned clear and windless. Two American climbers and four climbing Sherpas, the only people on the mountain, were able to make good use of the unexpected clearance and summited at 10.00am today. These fortunate six people are the first to summit Everest from Tibet this year. Well done to the Sherpas and the American climbers. This caught the rest of the expeditions off guard as everyone else was in ABC or BC waiting for the clearance expected in 4 days time. A full scale exodus from ABC to the Nth Col is now underway in expectation that the good weather will last for a few more days. Another storm is predicted for the 24th of May so everyone is aiming for the 22nd or 23rd. Let's hope the weather holds and the mountain allows us a chance to climb. This was to be Mark’s final diary entry. The Final Push On Sunday May 20th the SA Everest Expedition left their Advanced Base Camp (6400m) for their second summit attempt. This would see them at Camp 1 on the North Col (7100m) that night, then Camp 2 (7900m) on the 21st and at High Camp 3 (8300m) by the 22nd, which would see them ready for their shot at the summit (8848m) on May 23rd, assuming Chomolungma and the weather gods allowed it. A Prayer to the Moon Three days later, on the 23rd of May, news came through that Duncan had made it to the summit and that Mark had about 200 metres to go. This was great news for Duncan and there was a sense of optimism mixed with anxiety for Mark. I remember that night calling Mark’s wife Catherine to see how she was going. She was reluctant to say much and I sensed her anxiety. I went for a walk in the park after the phone call. The moon was out and as I walked I remembered a conversation I had with Mark about his night alone on Makalu, trying to get back to his high camp after David Hume fell to his death. He spoke of how he used the moon to keep his bearings until it became obscured by the Makalu Ridge. Then he had to focus on the positive voices in his head to guide him home. As I recalled this I looked up at the moon and said a prayer as I wondered whether the moon would be there for Mark this time? And now these three remain: faith, hope and love. But the greatest of these is love. 1 Corinthians 13:13 Excerpt from the book: The Spirit of Adventure Calls - A Compass for Life, Learning & Leadership Chapter 4 Triumph and Tragedy on Everest I imagined that night as I looked up at the moon, that Mark would somehow find the strength to inch his way, breath by breath to the summit. Part of me was excited at the prospect that he was so close to achieving his dream but like many of those close to Mark who knew how quickly triumph can turn to tragedy on high mountains, I did not sleep well that night. Climber from SA Reaches Pinnacle of His Career On the morning of May 24th, 2001 the local South Australian newspaper announced that Duncan Chessell had reached the pinnacle of his career by becoming the first South Australian to reach the summit of the world’s highest mountain at 9.30am on May 23rd. It was reported that his climbing companion Mark Auricht, was poised to emulate Duncan’s accomplishment. Mark was less than 200 metres from the summit when the Media asked his wife to comment. Catherine said that Duncan had begun his descent and that her last information was that Mark was on his way up. It might be an hour or as we speak she said. We’ll certainly be very relieved to hear when they are down. Dr David Tingay, the expedition doctor was also cautious, warning that Mark would be exhausted and dehydrated as he strove to climb the last few hundred metres to reach the summit. Two hundred metres doesn’t sound like much, but at the cruising altitude of a jetliner; where the oxygen levels and air pressure are not conducive to survival, let alone climbing through knee deep snow while exhausted, dehydrated and dis-orientated; two hundred metres can take hours... precious hours of life that is draining out of the body as the irrational mind says keep going, I’m almost there. Mark’s success was far from assured when the news broke. Meanwhile on the Mountain As most South Australians were reading the news about Duncan reaching the summit and that Mark was soon to do the same, they were unaware that Mark had already passed away that same morning, May 24th between 7.00―7.30am. Most of Mark’s family and friends received the shocking news of his death by phone during that day before it was reported in the news. It’s strange, but I can even remember the tiles on the floor where I was standing as I listened to the words I did not want to hear. A Difficult Message to Send The following day (Friday May 25th) a message via the SA Everest Expedition website from Duncan Chessell’s wife, Jo Arnold, confirmed early details. Dear Friends, I am deeply saddened to report the death at breakfast time yesterday, Thursday 24th of May 2001, of our good friend Mark Auricht, at camp two (7900m) on Mount Everest. It seems too early to speak about Mark, as the news is so recent. Few details are available at this stage but the Australian Army Alpine Association Team was extremely generous in extending all assistance to Mark. We wish them luck with their own summit attempts. Scott Ferris at Advanced Base Camp and expedition doctor, David Tingay have been an invaluable help at this difficult time. Duncan Chessell reached the top of Mount Everest early on Wednesday, 23rd of May, as did Tshering Sherpa. Duncan, Tshering and Pemba Sherpa, have now returned to Advanced Base Camp and are tired but well. Jo Arnold The last email I received from Mark was sent some weeks before on May 3rd while he rested in Base Camp after climbing to 7900m. As I tried to grapple with my disbelief, I hung onto the last words he shared with me:- Hi Wayne, hope all is going well in Adelaide for you... Thanks once again for your support, I think about you, your farewell words and your support often. Say hello to Gab and the kids and I look forward to sharing the stories with you in Adelaide. Cheers Mark Pieces in the Puzzle Like many of Mark’s family and friends we never got to hear his stories, only snippets from the expedition diaries and what little was reported in the news. In the days following Mark’s death it was unclear what had happened, but as days passed into weeks, the details of what happened that day on the mountain gradually emerged and the pieces of the puzzle for Mark’s family and friends became clearer. The two parties that know most about what happened are the SA Expedition members who were with Mark between the summit and High Camp (8300m) and the Australian Army Expedition members who looked after him during the morning of his death at Camp 2 (7900m). The following interviews bring to light some of these details. INTERVIEW WITH DUNCAN CHESSELL By Julian Burton―September 17th, 2004 Everest is so hard to climb because of the lack of oxygen and the cold. You are looking at about 30% of available oxygen compared to that at sea level. The temperature on its own wouldn’t present so much of a problem. It’s about minus 40-45, depending on the day which is not too bad if you have the right gear but if there is a lot of wind that is not good. The wind chill factor can kill you pretty fast. The lack of oxygen is the real problem. It slows everything down, including your thinking. The oxygen level in your blood stream drops considerably. So much so that if you were in a hospital in Australia and they tested your blood they would put you in intensive care. There is an incredible amount of effort required for each step at high altitude; which is the physical part of climbing, but then there is the mental part as well. Your physical and mental capacities need to match each other. That is the trick with climbing and mountaineering. If you have two columns and one has mental toughness and the other physical toughness; in climbing you want physical toughness to be slightly higher or equal to your mental toughness. If mental toughness is higher you will push yourself and push yourself to the point where you can’t go on and on a mountain you have to go on. You have to not only have enough to get to the summit but also enough in reserve to come back. On the way up a mountain you break your walking down. You might walk for 50 steps, then stop and breathe, focus again and then breathe as hard as you can for 30 seconds and keep going. Your lungs are just trashed, because you’re respiration rate is so high. By the time you get to the last five minutes from the summit of Everest you are down to focusing on taking 10 steps and then 8 steps. As soon as you start to go more than a very slow pace, you get straight into oxygen debt and you can’t maintain it. In front of you, you are looking at the snow ridge where the summit is. You keeping looking up at it every 30 seconds or so, take those eight steps, then look again to your goal. When I finally got to the summit of Everest with my Sherpa -Tshering Pande Bhote, it was pretty weird... I remember going “Oh, I guess this must be it then”. No bells or whistles went off when I arrived. The summit is about 3 metres long and about 1 metre wide with three faces converging at the top; one very steep and the other two moderately steep; with a patch of snow that is fairly flat on top. You end up on this tiny perch at the very top of the world where there are prayer flags, pictures and rocks that have been left by other people. I sat down and looked around for about an hour and twenty minutes. We came from the Tibetan side but now all of a sudden I could see the other half of the mountain and down into Nepal where there were tiny villages that I recognised in the distance below. At first it wasn’t too emotional... at the time you are focusing on what you have to do. For years you have been imagining it and visualising it and you pre-program what you will do when you get there. ‘If this happens I go to plan B, or this I use plan C’; so you have worked out what you need to do on summit day and are just rolling it out. It wasn’t until I called Base Camp on the radio that it first started to sink in. I said “Base Camp, this is Duncan calling from the summit; do you copy?” and the response came from Base Camp, “we copy.” I could hear in the background all these chants and cheers. I then thought to myself, “I have climbed it!” It was then that I realised that all the guys that had helped us get to the top were as happy, if not happier, than we were. I was tired and buggered from the climb, so I didn’t fully take it in but I thought “I’m finally here, I have been waiting to do this for 10 years.” Base Camp called Australia and the rest of our team on the mountain, they were all stoked. Everyone had put in such a big effort. I realised then that now that we’d actually gone through with our dream and I’d become the person standing on the summit, there were all these other people who shared in the dream with us: our fellow climbers and Sherpas; the base camp people; our sponsors and our families who had supported us on our way there. It was a victory for everyone and I assumed that Mark would soon be joining me. I guess what I had achieved did not really sink in for about a week, partly because Mark and I had planned the whole expedition together and I had visualised a summit photograph with Mark, and our arms around each other’s shoulders, thumbs up, smiling and grinning... ‘Beauty, well done, off we go, let’s walk down now.’ So I had that picture in my mind and I sat there and waited for Mark for one hour and twenty minutes. I looked at my oxygen bottle and it was going down and down and I knew I could not wait too much longer. I had to go. It wasn’t the completion that I had pictured. I hadn’t visualised it just being me standing up there without Mark, going ‘yahoo!’ I was always anticipating it to be at least the two of us and our Sherpas there together. That is what we had worked on for years before that day. Picking Mark up on the way down was the greatest feeling of disappointment. He was pretty happy for the two of us who got there but for Mark, this was probably going to be his one and only shot at Everest. It wasn’t an option for him to come back in another year, so he was bitterly disappointed at having to turn around. I remember on the way down we were talking about how we could set up another summit bid for him to get another shot in a few days time but we kind of all knew deep down that the season was about to close, the bad weather was about to come in and it was going to be pretty unlikely that he would get another shot at it. It would have been our third summit bid on that expedition. On our first try the weather came in half way up and we didn’t get anywhere near it so we came back down and rested for a few days and then the second attempt was when I and my Sherpa friend Tshering Pande Bhote made it to the top. For Mark, it was very improbable now. Mark’s mental toughness was very strong and his physical ability was usually very strong too but on this day, having had a slight cold which may have reduced his physical capacity to cope with high altitude, his physical strength wasn’t able to match his mental strength and will to get to the top. When Mark got down to the high camp at 8300m with us he was very tired. We all were, but Tshering and I were in a better state than Mark was. With this in mind we asked Mark if he wanted to go down to the lower camp where the impact of altitude would be significantly lessened. It’s always the best option to get down to a lower altitude where there is more oxygen, especially if you are already experiencing early signs of altitude sickness. Tshering and I who had been to the summit were low on water and needed to stop at the high camp to melt snow and re-hydrate... and since Mark wasn’t feeling so good we offered him the option to continue down to the lower camp where there was also more tent space, a support Sherpa with another oxygen bottle and a radio. Had we all gone down, there wouldn’t have been much room in the tent at the lower camp at 7900m. It was about a one hour walk on fixed lines down to the lower camp. The rope actually went passed the door of our tent and we had our support Sherpa in the tent below with a radio so that if Mark needed to call for assistance he could do so on his radio. All of our radios were on standby if he needed a hand. So we thought that everything was covered. My best guess as to what had happened on the way down, was that Mark’s altitude sickness had started to affect him later in the day as he descended and he was so fatigued and disappointed that he no longer had the energy that had been driving him up. I’m pretty sure this was the case, based on a lot of other expeditions and seeing people in a similar place. I think he probably sat down on a rock just before sunset and just went to sleep. When he woke up he would have been out of oxygen and his altitude sickness would have gotten worse, to the point where his thinking would have been affected. This might explain why he didn’t use the radio and why he missed our camp as he continued down the rope. He must have walked straight past our tent and kept going before he bumped into the Army expedition’s tent at about 1.00am. It had taken seven hours to walk down something that should have taken an hour. He must have been out for a long time so I knew his oxygen had run out. It is my understanding that he bunked in with the Australian Army Expedition for the night and they didn’t think too much about it. They thought he was just tired and a bit out of it. The next morning they said “Right mate we’re heading off to go up to the summit.” According to them, Mark was a bit slow and floppy and not too together. He got out of their tent and was sitting against a rock and just put his head down and stopped moving. Up until the tragedy of Mark’s death, every other aspect of the expedition went pretty well - we nailed all of our small and medium goals for the expedition and everything rolled out pretty well as planned. We’d already had a very fulfilling expedition prior to summit day. The one person who was missing at the top was Mark and he got within 150 metres which is an amazing achievement in itself. Interview shared with permission from Duncan Chessell Army Expedition account from lower down the mountain Unfortunately, Duncan Chessell wasn’t with Mark when he died, so he could only piece together the events after Mark left their High Camp in the late afternoon of May 23rd, from accounts provided to him by the Army expedition members who looked after Mark the next morning. When I first wrote a draft of this manuscript 10 years ago, I felt that it would be helpful to include excerpts from media interviews done with the Army Alpine Association (AAA) team members to fill some gaps in my mind and the minds of others who wanted or needed to know and understand more. I recently decided however, that it would be more accurate to get first-hand accounts from those who were involved. Even though some of the memories have faded after 15 years, those who were on the spot have some vivid memories etched in their minds. I interviewed Zac Zaharias, Brian (Henri) Laursen and Tim Robathan, who all played a significant role in looking after Mark on the morning of May 24th, 2001. I also had a chat with Bob Killip who helped with the return of a precious item to Mark’s family. Following is a summary of their recollections, sewn together with details about the events of that day and May 25th, that were published in 2006 by Peter Maiden in his book, Anzac Day on Mt Everest. I have not used military titles with the names of the AAA team members, most of who were serving in either the Australian Army or Air Force, because rank was irrelevant on the mountain where all humans are equalised by the laws of nature. Leadership though, was tested many times in the case of Zac Zaharias, the Leader for the AAA Expedition. For the full account of the army expedition go to Peter Maiden's book (I include a little more of the army story but Peter's book is an excellent account of what happened to them.) It was a tough expedition, having to deal with death on numerous occasions. Zac Zaharias AUSTRALIAN ARMY ALPINE ASSOCIATION EXPEDITION STORY The AAA team members had gotten to know Mark and Duncan quite well as they shared space at their base camps. Despite being on different schedules while setting up their higher camps and going for the summit, they spent quite a bit of time together. Brian (Henri) Laursen―pronounced ‘Lawson’ (hence the nickname Henri), told me that the South Australians were welcome and regular visitors to the Army Mess Tent. Tim Robathan also shared his recollections of meeting Mark and Duncan and becoming friends as they spent time together at BC and ABC. I met Mark at Everest Base Camp, along with Duncan and the rest of their team, said Tim. We all became instant friends. We were all Aussies about to climb Mt Everest, he said. We spent most days at Base Camp hanging out together and I recall chatting to Mark a lot and really liking him. I was 23 at the time, so I was fascinated by the climbs that Mark had done, particularly Makalu. Some nights I'd be in Mark and Duncan’s tent watching movies on their laptop with them, while other nights they'd be in our mess tent playing cards, chatting, or having a drink. We became good friends. Unexpected Rendezvous Prior to his unexpected rendezvous with members of the AAA Expedition down at 7900m (AAA’s Camp 3 / SA’s Camp 2), Mark was descending with Duncan as we know, down the North Ridge which lead from the summit of Everest to their High Camp at 8300m. Along the North Ridge, all climbers have to negotiate three so-called ‘steps’ which are steep and technically difficult rocky sections that must be scaled slowly and carefully, leaving ascending climbers bent over double and breathing like a fish out of water, and descending climbers feeling anxious as they inch their way down to safety. As if their journey back to the shelter of their High Camp wasn’t long enough, Mark and Duncan had to wait in line behind other climbers for over an hour in two places as they climbed down narrow ledges. When they finally got back to their High Camp, we know that Mark decided to continue down to lower altitude, while Duncan and Sherpa Tshering Pande Bhote stopped to re-hydrate and rest. It was 5.00pm and the walk down to Camp 2 at 7900m should have taken Mark only 60-90 minutes. Eight hours later, at 1.00am, the Army’s Zaharias, heard something outside his tent... Members of AAA Team One that were camped there that night, were Zac Zaharias and Tim Robathan who shared a tent, and the other pair were Michael Cook (Cookie) together with Brian (Henri) Laursen. These four were to be the first of three AAA Expedition teams to attempt the summit for their expedition and had planned to get as restful a night as possible, in preparation for climbing to their Top Camp the next day. At 1.ooam Zac Zaharias remembers hearing someone outside the tents. The night was pitch black and super windy as Zac stuck his head out of the tent into the chill. Spindrift threatened to fill their tent with snow. Zac was concerned enough to get his boots on and went out into the freezing conditions to discover that it was Mark Auricht stumbling around, trying to find his tent. Fortunately the wind had blown the fixed rope over the top of Zac and Tim’s tent, so he bumped into it as he followed the life line. Mark looked knackered and confused, Zac recalls. He wasn’t sure whether his tent was above or below ours and I didn’t have a clue, so we thought it best to take him into our tent and help him warm up and re-hydrate with a cuppa. Perhaps then we could help him back to his tent. A certain Samaritan came upon him. He felt compassion... brought him in... and took care of him. Luke 10:33-34 Mark was completely exhausted, said Tim. We were trying to understand what he was doing. It was really crowded in the two-man tent with the three of us on a not-so-level snow slope. I crouched at one end, while we got Mark into a sleeping bag for warmth, Tim said... I started the stove up to begin melting snow to get water for Mark. At sea level this is an easy process, but at our altitude and in the temperatures we were in it was hard work. It took about an hour to get 1 litre of water. As I was getting water heated we'd sit Mark up and get him to drink. Zac gave him his water as well. We were all suffering from altitude, and at the time Mark appeared to be more exhausted than anything else. He managed to explain to us that Duncan had made it to the summit but that he had to turn around and he left Duncan and the Sherpa at their High Camp at dusk I think. It should have been maybe a two hour descent at the most, but he’d been going for maybe 7-8 hours and had run out of oxygen. No Silent Night Zac reports that while they were giving Mark a cuppa and he was relaying his story, he seemed lucid and there were no obvious signs that he was critically ill. He was exhausted, dehydrated and talking slowly but that was to be expected at that altitude, especially after what he’d been through. At the time we thought he’d be okay after warming up, re-hydrating and having a good rest, said Zac. I remember him going back outside again to have another go at finding his tent. He staggered and fell over, so I suggested he spend the night with us in our tent, even though there was little room. He had a better chance of finding his tent safely in the morning, said Zac. So they rode out the rough night in the cramped tent together, with Mark wedged between Zac and Tim. There was no ‘heavenly peace’ that night! The Dawn of Silence When sunrise came, Zac and Tim began the slow process of getting their boots and other gear on, so they could let Henri and Cookie know what was going on. Hopefully Mark was feeling better and they’d be able to start the climb to their Top Camp. Zac got out of the tent first, said Tim. Then we moved Mark to the entrance of the tent and stuck his legs out so we could get his boots and crampons on. He was a bit incoherent and just wanted to lie down. Mark was leaning on his elbow, talking slowly and drifting in and out a bit as he was trying to get dressed, Zac said. I was saying to him, ‘Here’s your glove, make sure you put it on’... He was responding and doing things under his own steam, but kept drifting off to sleep. While I was glancing down, putting on my boots, I talked to him but got no response. I looked up to see that he was lying down with the top half of his torso inside the tent and his legs outside, Zac said. I checked him for a response but there was none. Tim recalls getting a bottle of oxygen set up and putting the mask on Mark to see if it would help him but he was lifeless. At the same time we yelled out to Henri and Cookie for assistance, said Tim. Henri remembers having no time to cover his own hands, so he had difficulty detecting a pulse, whether Mark had one or not. My hands were like cold hard plastic, he said. I checked Mark’s pupils too but they were not responsive. It was difficult to determine whether he was still alive, so I started compressions, while Zac took care of Mark’s airway, said Henri. After some time trying to revive him it was obvious that Mark wasn’t coming back and so I had to ‘call it.’ I think it was about 0700 or so. Tim Robathan distinctly remembers the moment: We were holding Mark when he passed. It was pretty devastating as we sat there with him in silence. Shockwaves Despite other tragedies that Zac Zaharias had experienced previously, he said he was taken aback by Mark’s death. I was shocked because I’d never seen this happen. I’ve seen all sorts of accidents in the Himalayas but I’ve never seen someone die in front of me before, he said. Tim and Zac then commenced communications with the other team members further down the mountain. Tim asked his Base Camp to see if they could communicate via the SA Base Camp to get a message to Duncan on the radio but wasn’t sure if they were able to reach him. The first that the rest of the expedition heard about the drama unfolding 1000 metres above them, was when Tim Robathan rang down to Bob Killip at Camp 1. It was just after 7.30am when Bob took the call. He shook his head with sorrow as he relayed the message to the others - Mark from the South Australian Expedition just died at Camp 3 in the arms of our boys... He slipped into unconsciousness fifteen minutes ago. As a flurry of questions went back and forth between team members around him, Bob was kneeling like a silent statue inside his tent, staring into space in disbelief. Bob was clearly moved by Mark’s death, as were most of them who had gotten to know Mark. Tim said that when he made the call to ABC he was deeply upset but tried not to show it. I got to know Mark pretty well during the trip and I really liked him, so it was a difficult moment, he said. The issue now was whether to try and bring Mark’s body down or leave him on the mountain as was the usual practice at that altitude where it is very difficult to bring someone down without risking the lives of those who attempt the task. We really couldn’t take any decisive action until we heard from Mark’s family, so we wrapped Mark in a tent-fly and waited for Duncan to arrive or to hear from the family, said Zac. There wasn’t much more we could do. Henri Laursen and Michael Cook were ascending above the tents where Zac and Tim were with Mark, when Duncan Chessell came down with his Sherpa looking for Mark. Henri gave Duncan the distressing news of Mark’s death. According to Henri, Duncan was having a hard time processing it at first. He’d heard some of the radio chatter but didn’t seem to be fully aware of the gravity of the situation until I told him, said Henri. Duncan was in shock and disbelief as he continued down to find Mark. When Duncan arrived at about 0800, he was just stone-faced. I guess he had the shutters up, said Zac. He sat down next to Mark and spent quite some time grieving. Duncan had now seen for himself that Mark was gone. We just sat there in silence and cried. Eventually contact was made with Mark’s family and the decision was made to lay him to rest among the mountains he so loved. Both Zac and Henri told me that there really wasn’t anywhere to bury Mark at that location, so the best they could do was move him off the main ridge onto the western face of the mountain, where he could be placed in a rock fissure not to be disturbed by passing traffic. Becoming One with Chomolunga I recently spoke to Bob Killip who had taken the radio call at the lower camp that morning and was on his way up the next day. Bob said that he didn’t remember much about those few days, except for the sad task of having to remove Mark’s wedding ring from a necklace he was wearing, so that it could be returned with other personal effects to his family. Bob said that he found this difficult. He also remembers being there when a group of Sherpas from Russel Brice’s team helped to move Mark to his final resting place. Mark was laid to rest on the western face, in the direction of the setting sun. He would over time, become at one with the mountain, covered in snow or taken by an avalanche back into the arms of Mother Nature. Like a burial in the ocean or ashes taken by the wind, his spirit would become one with Mother Goddess of the Universe. I took to the mountains to find myself. In fear of death I did my best. Now all fear is laid to rest. The Ascent of Angels Those who attended to Mark at 7900 metres on Everest would probably squirm with embarrassment at being referred to as angels but I think it is an apt description for those who put their own needs aside to help others, especially in extreme circumstances. According to those who know him, it seems that Zac Zaharias rarely participates in an expedition where he does not help somebody in distress. He left himself seriously dehydrated after giving his drinking water to Mark, and as the rest of the team continued up the mountain after doing what they could, Zac remained with Mark to keep vigil over him until Duncan arrived. He arrived quite late at his Top Camp where for the second night he had almost no sleep. The AAA Team’s readiness for the summit was less than ideal. Later that night they prepared to leave for the summit but delayed their departure due to misgivings about the weather. Henri Laursen and his two Sherpas (Chhewang Nima and Ngima Nuru) eventually led the group into the night, after initially climbing with Michael Cook until Cookie was set back by a problem with his head torch. Cookie and Zac ended up behind Henri, with Tim Robathan following a short distance behind them. It is not uncommon for high altitude climbers to end up being spread apart due to differences in how they feel on the day, variation in pace, frequency and duration of rest stops, issues with gear, and having a staggered departure due to the fact that just suiting up and getting out of the tent takes time. At that altitude you can’t stand around waiting for too long, you need to get moving, saving oxygen and time for stops later. Pivotal Decisions Tim wasn’t happy with his rate of ascent and didn’t like the look of the weather when he got to the first step and saw that Zac and Cookie had already climbed it. His intuition told him that he needed to turn around. He had set a turnaround time for himself and knew that he wasn’t going to make it... I really wanted to reach the top but wasn’t prepared to risk my life, he said. As Tim took his decision to turn around, the other three continued up over the second and third step. It is very technical climbing at that altitude when the mind is not sharp and fatigue is setting in, not to mention the weather. Cookie said the second step is possibly the most daunting obstacle on the north side of Everest, at the top of which is a vertical face. As Cookie continued winding up through the rocks and snow on the ridge, he stopped to wait for Zac to catch up. Time was ticking away as they were about to start climbing the final snow slope to the summit. They had slowed down now, the weather was deteriorating and it was getting close to their time limit. There was still a long way to go as they wondered whether they should continue. A night on Everest near the summit without a tent and sleeping bag or negotiating the rock steps in the dark where they might get caught on the ridge in a storm, were not probabilities they were prepared to dismiss lightly. By now they were the last climbers on the higher stretch of the North Ridge after Henri Laursen had passed them on his way down from the summit, and they felt very isolated. Cookie was sitting there at over 8,700m, the highest man on earth at that time, and Zac was climbing up to him. They were no more than 150m from their goal, which was about where Mark was when he turned around after Duncan came down from the summit. As Cookie sat in this spot, so tantalisingly close to the summit, he had already realised a dream (what was another 150m in the scheme of things!). He may not appear in the historical records as an ‘Everest Summiter,’ but he had overcome the three most technically difficult sections that confront climbers on the North Ridge and he was still alive. To continue might put him in the history books but would probably kill him. He had made up his mind that this would be his summit today. Zac hadn’t quite got to the same pivot point yet and wanted to push on. Let’s just go on for one more hour, we’re so close, he said. By then it would be 3.00pm and even if they did reach the summit, they would face hours of difficult descent. Cookie agreed for the moment, but remained where he was at the edge of the snow slope, as if it were a shoreline to deeper waters. He watched as Zac waded into the waist deep snow. After 20 minutes Zac had only managed to make about 5 metres of progress. Cookie pulled his oxygen mask off and yelled out to Zac to come back. They both kept looking up at the summit... it was so close. Come back to the rock, please Zac, and let’s talk. It’s not for us today mate. After assessing their situation as rationally as you can with impaired thinking and summit fever, they reluctantly turned around and headed back to safety. The Challenge of Morality There is more of this tale to tell but you’ll have to read Peter Maiden’s book Anzac Day on Mt Everest,to get the whole story. The point of sharing this much of AAA Team’s push for the summit after helping Mark, is to illustrate the challenges of decision making, teamwork and leadership in extreme environments, and also to acknowledge that these four men somewhat sacrificed their own chances of reaching the summit to look after Mark as best they could. Unfortunately they couldn’t save his life but at least they did what they could and delayed their departure long enough to ensure that he was laid to rest with some semblance of dignity. There are other bodies on Everest that have not been offered such respect. We climb by ourselves, by our own efforts, on the big mountains... Above 8,000 metres is not a place where people can afford morality Japanese climber Eisuke Shigekawa There is probably some truth to the above statement, in circumstances where trying to help someone else in such a challenging environment would threaten one’s own survival, but for me, Zac Zaharias, Brian Laursen, Michael Cook, Tim Robathan and other members of the AAA Team, together with Sherpas from Russell Brice’s American Himex Expedition who helped to lay Mark to rest, demonstrated that there are moments when morality can indeed survive on high mountains. In Part IV of my book, I tackle this question of morality and values in more depth, with regard to leadership. It seems that it is not as straight forward as we’d like to think, especially when competing priorities prevail. One and All Brian (Henri) Laursen was the only one from the AAA Team to physically reach the summit with his climbing Sherpas Chhewang Nima and Ngima Nuru. When Henri arrived at the top at 11.30am on May 25th, there were eight other climbers there who had summited from the south side. Henri had 35 minutes on the summit so after the others left, he did get some time alone on the patch of snow at the highest place on earth. While his two Sherpa friends watched silently, he knelt down and gently placed a sprig of wattle on the snow. After the Annapurna tragedy, the AAA Team had been given this wattle from Governor-General William Deane’s garden in Canberra. A small white card with the names of the three who were killed in the avalanche, signed by Sir William Deane with his condolences, was attached to the wattle sprig by a green ribbon. The Governor-General suggested that the expedition could take it with them up the mountain and place it at the highest point that they were able to reach. It was decided the night before the group of four departed from their Top Camp that Henri would be the one entrusted to carry it because he had been moving well up the mountain. Back at Base Camp the whole expedition team had previously had a discussion about the composition of their teams, during which Henri essentially said: If some of us get to the top, we all get there. We’re all part of the summit team. When one man climbs, the rest are lifted up. When We Were Kings―Brian McKnight. As it happened Henri was the ‘one man’ to get there in the end and managed to take Peter, Michelle and KC with him all the way to the top. He fulfilled his commitment to them and the rest of the team when he placed the small but significant memento on the summit of the world. To have reached the top was a very emotional experience. It was a huge relief, he recalls. Physically and emotionally, I was drained. The emotion that he felt on the summit was a mix of relief and elation for having finally arrived there after a 9 year journey, and grief for the lives lost. Henri sent a heartfelt message of thanks to the support teams below him, before sticking his axe in the snow, then hanging his backpack, water bottle and camera over it. He could then finally take in the moment he had been dreaming of for almost a decade. The depth of emotional intensity that Henri experienced during those few minutes of solitude at 8,850m must have been palpable by his two Sherpa friends, as they too had experienced the journey of tragedy and triumph. When Henri returned from the summit, weary and euphoric, his emotions were up and down as he recounted his experience. He was asked if he would come back. I would think hard before coming back, Henri said, as he visibly choked back his emotion. This mountain throws everything at you; horrendous weather, deep snow, and rock climbing all the way to the summit. You’ve gotta have your wits about you to make sure you get back to your tent, he said. At 8000m it is a different game. To have finally overcome all of that is a pretty good feeling... climbing mountains is an emotional thing, he said as his voice broke. When I finished interviewing Henri on the phone, he said he had two young boys now and he had given up climbing big mountains. I couldn’t put them through that, he said. Tim also said that the 2001 Everest expedition had a huge effect on him. It totally changed my life, he said. It took me two years before I went back into the mountains. The psychological scars have an impact. The hardest thing was coming home. No one can really understand what you’ve been through. One minute you’re below the summit of Everest struggling for life and 2 weeks later you are in suburbia. You think you’re okay but small things can bring it all back, Tim Said. I still think about Mark now and again, usually May 24 each year. Mark's passing had a pretty big impact on me. Sacred Mother Mountain of old Keep loving care of our brother’s soul. Wayne  Mark Auricht & David Hume were the first Australian's to summit Mt Makalu on May 8th, 1995 This is Part 2 of their story... Please read Part One in the preceding blog post - before continuing the story here..... ....So here we are, a couple of proud Aussies sitting at about eight and a half thousand metres above sea level where jet planes fly. I felt an incredible sense of privilege at getting this half hour on top of the world. All the factors had come together for us and we were finally there. I remember feeling a great variety of emotions. One just of relief at having finally got there, after all the preparation we’d done at home and in the mountains, all the lugging of gear up the mountain and dealing with the hardship of actually just functioning at this altitude. There is an enormous amount of relief knowing that going down will be significantly easier. The next feeling I remember was an enormous sense of appreciation for my physical body for getting me to this incredible spot. I’d punished it unmercifully beyond anything I’d done before and it had done everything I’d asked of it. And then the next more overwhelming emotion was anxiety, just an incredible amount of anxiety. We were way too late to be sitting on this mountain at this time. We still had to get back to Camp 4 and there was only about an hour of daylight left so I knew it was going to get dark and I knew that descending, despite being physically easier, was the most dangerous thing we had yet to do. The unfortunate thing about summiting any mountain is that you know that the moment you get there your head’s thinking about heading back down. Time started to go incredibly quickly now... the hands on the clock just took off... we were on the summit for about half an hour and in that time took a photograph of each other, panned the video around and that was a half hour gone. We were already starting to move a bit more slowly due to the altitude and fatigue as well. The last thing I remember doing was standing up with my arms outstretched above me (as per my company logo9) and then I quickly sat back down and we made our way off the summit. Descending Into Darkness We got back to the false summit and it was dark. We’d been climbing with our head torches all that morning, which is an okay way to climb on the snow and ice... your torches just glow beautifully... but now our torches were down to a dull glow on the ice. We had to traverse back along the summit ridge and find the steep gully that would bring us back onto the ice field above Camp 4. It was incredibly important that we found the correct gully because we had a couple of ropes there leading us back to Camp 4. Had we gone down the wrong gully we would have had no idea of the terrain we’d come into. At about 9 o’clock that night we found the head of the gully and our footsteps. We were relieved to know that we were back on track. I remember sitting down at the top of this gully to have a rest... imagine now a big slippery dip of ice with a vertical rock step of about 50 metres, then another ice field... another rock step... then another ice field leading down onto the glacier below... all of it about 350 metres in height. Here we sat resting for a moment, not talking, hardly wasting an ounce of energy on a thought. One of the things I remember about altitude is that there’s no daydreaming. I could focus on a thought... I knew what I was doing... I was absolutely clear on what I was doing... but there were no extraneous thoughts happening at all... no extra conversations... so I don’t remember talking to David as we sat there. We then got up and I started heading down. I’m facing out now, and I’m walking down with my crampons gripping the ice and David behind me. All of a sudden this incredible impact took my feet out from under me. It was David sliding out of control down this ice slope. Fortunately he hit me low enough that my legs flipped out from under me but I was able to spin around and use my ice axe to stop my fall... just in time to look over my shoulder at David going like a steam train over this rock ledge that was maybe 20 metres below me... and just like that he was gone! It was shocking and unreal... “is this really happening?” It felt unreal but again my mind did not waste thoughts. It was immediately very clear that I just had to do what I had to do to get down. In hindsight it was surprising that I wasn’t overwhelmed with panic... I got very nervous though and instead of facing out I turned around and used my tools to back down, which is the safer way to go but much slower. I got down to the rock step where we had a piece of rope only 20 metres away. This piece of rope may or may not have saved his life. I might have been in control of him... but when I think about it, had we been tied together I would have gone with him. It’s incredible the speed at which the ‘what if’s’ go through your head but it can’t change what has happened and I must focus on what I have to do now in this moment. I abseiled down this rock step and saw the eeriest thing that still sticks in my mind... when you carry an ice axe, you have a lanyard that runs up and sits around your wrist in case you drop your axe so that you won’t lose it down the mountainside. When David fell and landed on the ice below his axe must have caught on the ice and skun his glove off while he kept going. So you can imagine an ice axe just hanging out of the ice with the lanyard and a bare glove on the end of it... just swinging. When I abseiled down I was confronted by this ice axe just hanging there... it was an awful sight... but it also set my mind crazy thinking for a moment that maybe he was alive? I’d actually come to the conclusion by then that he was already dead before he went over the edge. What I think happened was that he had a cerebral oedema... an accumulation of fluid on the brain. Cerebral Oedema is a condition caused by high altitude where fluid starts leaking from cells into spaces it shouldn’t be and squashes the brain, causing the victim to lose consciousness which is often closely followed by death as the brain stops functioning. I think David just passed out after he stood up and started walking. He might have already been dead when he fell over and took off down the slope. The reason I think that was because he was on his back and your initial response as a mountaineer is to roll straight onto your front and use your axe to stop... but he was on his back... and he said absolutely nothing... he was completely silent. So I hope that he was unconscious when he went over the edge and I really believe that was the case. However when I saw his axe I thought for a moment... “Was he alive?... did he try to stop himself?” Then I continued down to the bottom of this 350 metre gully. It was quite obvious where he landed, and he continued off down the glacial field and ended up in a crevasse that would have been some 150-200 metres down the glacier. Now that I was at the bottom of that gully I had to cut across the glacier to get to Camp 4 but the path of his descent had continued down the glacier... so then I sat and thought... “Do I go and look for him, or do I go home?” Fortunately I made a good decision at that point and I went for home. I figured there was a one percent or less chance that he would have survived that fall, and if he had done, there was nothing that I could have done for him. In my head I remember thinking (and maybe this was just to help me make the decision) “I’ll come back... I’ll go to Camp 4 and rest up then come back to try and find him”... not expecting to find him alive, but expecting to put him into his sleeping bag. We’d had a conversation in the Blue Mountains about death and as a group we decided that if a person died we’d put them in their sleeping bag and lower them into a crevasse... so all that was going through my head was “I’m going to get a sleeping bag, come back and put him in it...” so I continued back across the glacier. Following the Inner Compass By now my torch was almost out and the moon had gone behind the Makalu Ridge, so it was really quite dark. This made it difficult to pick up the trail of my footprints that were now barely visible between the shadows cast by odd shaped bits of snow, threatening to lead me astray. I seemed to walk for endless hours down this ice field and I remember distinctly two voices, one on each shoulder: one saying “you’ve gone too far, you’ve gone too far... you’re lost”, and the other voice saying “you’re doing fine just keep going, you’re doing fine, just keep going” and these two voices were just battling... I don’t even know the time frame but had I lost my way then it would have been all over. Eventually I was enormously relieved to find the fixed rope which led back to Camp 4 so I knew then that I was still on track and almost home. I clipped onto the fixed rope which cut diagonally across this large ice field and began abseiling down. Previously on the trip I had damaged my left ankle, twisting it quite badly. As I abseiled across the ice field with all my weight on my left foot, my ankle gave way and I tumbled off the slope and around the ice face; a sheer wall of blue water ice dropping down into a dark abyss. In my mind I could see myself falling off the ice field in slow motion, plunging sideways on the rope for what seemed like eternity before smacking into the hard cold wall of ice which brought me to an abrupt and painful halt. My life was now literally hanging in the balance by this rope I was attached to and the ice screw that secured it tenuously to the mountain side. As I pictured the knot attached to the screw I thought “will it hold or will I fall helplessly into the darkness?” Then a strange thing happened in that moment... I reached the point where I completely let go... I had no fear and I didn’t care whether it went one way or the other... I distinctly remember that feeling. Then... “nup, it hasn’t gone... great... I’m still here!” After feeling the rush of survival I realised now that the rope was anchored at the top and anchored again at the bottom of the ice field. Because I’d swung sideways down the side of this wall of ice, I had fully loaded the rope putting tension on the whole system and I was now jammed on the rope... locked off... hanging over this black abyss. Letting Go I’ve been on the go now for about 25 hours and into my second night without sleep with only a litre of water, a handful of nuts, some muesli. Again I just ‘let go’ and relaxed, thinking “Okay, I’ve got to solve this.” This timeless moment is like the void between the trapeze bars where the outcome is uncertain – faith, hope and trust are all we have to rely on. All we can do is let go and be at peace with it. Then came an answer from the silence... the only way I could solve this was to turn myself upside down and haul myself diagonally down the rope, feeding it into my abseiling device... like abseiling upside down basically. I did this with painstakingly slow progress until I eventually made it back onto the snowfield and collapsed. After recovering from this exhausting ordeal I got back onto my feet and completed the journey to the safety of Camp 4 where I collapsed into the tent that I’d left 27 hours earlier. Then I spent this incredible 12 hours waiting for David to turn up... it was the strangest thing... I was now also on my third night either above or just below 8000 metres. Above about 5500 metres your body is gradually just shutting down and the higher you go the more your body just can’t survive as the oxygen level goes lower and lower. No one to my knowledge has survived longer than 4 days at 8000 metres... I was now on the end of my third day and was still thinking foolishly “I’ll go back and find David.” So I spent that whole day and night there before loading David’s sleeping bag into my pack after which I left the tent and started to head back up towards where he was. I climbed for about an hour and probably only covered a distance of 20 metres. There was just no way that I was going to get back... so again I made a good decision... I had to get off the mountain. So I turned around... went back... dumped David’s gear in the tent and headed back towards Camp 3. Fortunately it was that big bowl type section and after a bit of steep stuff I was onto some reasonably good snowfields. This was fortunate because I couldn’t walk further than about 20 paces without falling over. To keep myself going I started counting steps... I’d get up to 18..19..20 and fall flat on my face in the snow. Then I’d lie there and think “I’ve got to get more than 20”... so I’d stand up... 18..19..20..21... doof (a face full of snow)... and then get up and do it again. I was in no pain... I felt fine... I was warm... it was bizarre... I just felt great... probably the endorphins charging through my body again. The Temptation to Sleep Anyway, I was almost back at Camp 3 when I’ve fallen over again and I’m lying in the snow drifting in and out of delirium, thinking “It would be so nice to stay here... warm... peaceful... blissful sleep...” And then as my gaze follows the moonlight across the surface of the snow, I find myself looking directly at the frozen Polish guy with the red jacket flapping in the breeze about 200 metres away. So then, still lying there in the snow I remember suddenly thinking “Get up Mark... get up Mark!” It was probably good timing seeing that guy. In a way he just may have saved my life, as I was about to surrender to the snow... but the ‘Icey Pole’ reminded me of what would happen if I stopped for too long. So I got up and kept going, eventually making it to Camp 3. In the same way as the Polish guy had turned up when I most needed it, another incredible thing happened on my way down to Base Camp. As I recall it, there happened to be some Sherpas who were trekking with some other people up around the Makalu region who had heard about what happened. These three guys who I didn’t know from a bar of soap, didn’t have any gear or anything... they put some food and some gear in a pack and climbed all the way up to Camp 1 to meet me. They made me some soup and then guided me down in the dark that night with a torch... it was just sensational! I got back to Base Camp and these guys disappeared. I never saw them again! Spiritual helpers are often anonymous Anon I remember feeling really different now. I was having these incredible swings between this great excitement at having achieved what we’d set out to achieve, and this incredible upset and anger about what had happened to David. I was blaming the Basques... I guess I had attached his death to them and that was the way it was in my head... so I was quite angry and my moods were swinging radically. I had also lost 10kg in bodyweight... mostly muscle digested by my own body to keep me alive. I was by now this skinny, ravenous rake. Into the Arms of the Bear I’m almost home now... walking into Base Camp when the Basques leap out of their mess tent... “aahhhh come in!”... I’ve caught them at their summit celebration meal... so they’re all sitting around this table with all this food and grog... and I haven’t eaten a decent meal in a week... I’ve had one night’s sleep... gone for three without... had one ravaged night on the mountain... I’ve turned up in the Basque tent... whisky straight into my hand as I sit down... “Strong Man... Strong Man” the Basques say as they pat me on the back... and this plate of food arrives with a mound of rice, chicken and lentils... so that’s gone... phoom... disappeared down the gullet in about three seconds. I managed to get down another two plates full in succession. As I scoffed down all the food and drink I was picking up this mood in the tent...so I asked one of the Basques who could speak reasonable English, what the leader of their expedition was saying... “What’s Juanito saying?” He started to shuffle in his seat and was getting quite uncomfortable. I asked again “Tell me what he is saying?” His reply was astonishing... “He thinks you should’ve shared your sleeping bags with us at Camp 4” he said. In a flash, all the hair on the back of my neck just stood up... and I’m out of the chair screaming at this guy. As I head around the table toward him, he leaps out of his chair and just grabs me... He gives me this big bear hug and says, “That’s it, we’re not going to mention it again”. He then put me back down in my seat... and he sat down. It didn’t get mentioned again... but boy I was volatile... so I finished my meal... staggered back down to Base Camp... walked in and it was just elation... I said “I’m home... Thank God” The New Comfort Zone .... I’ve collapsed in my tent... and lo and behold... at about 3 o’clock in the morning the alarm bells go off in my tummy! So I leap out of bed... bear in mind the toilet tent is about 30 metres across all this rocky terrain... so I’ve put my ugg boots on... thermal underwear... and I’m sprinting!... across these rocks and I just wasn’t going to make it... I’m trying to get my pants off... and it was just too late... all this stuff just poured down into my ugg boots... down my legs and through my pants. So there I am standing there with all this shit everywhere... full moon in a clear night sky shining down on me like a spot light on a stage... and I remember just thinking... “what have I become?”... “how basic is this?”... so I pulled it all back up and got back into my sleeping bag and went to sleep... that’s how basic things had become... “I’ll fix it in the morning”... my comfort zone was different now! On May 8th, 1995 David Hume and Mark Auricht became the first Australians to climb to the summit of Mt Makalu. David will be remembered for his happy disposition, strong leadership and sense of humour. Beyond the triumph and tragedy in the Himalayan mountains, this book is also about the journey that takes place within all of us, when we explore the limits of our self-imposed boundaries. May it serve as an inspiration and a compass for future leaders, adventurous souls and explorers of human potential. Click below to read the whole book The Spirit of Adventure Calls: A Compass for Life, Learning & Leadership David Hume on the Summit of Mt Makalu - May 8th, 1995 Part One - The First Australians to Summit Mt Makalu

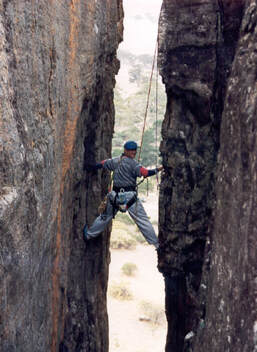

In my last blog - Facing the Truth of Impermanence, I shared an excerpt from a book I published in 2017, as a tribute to my friend Mark Auricht. The truth of impermanence is a double-edged sword: the edge of loss and all of the pain and fear that human beings experience because of it, and the edge of freedom, peace and truth that we experience when we let go. Mountaineers come face to face with the truth of impermanence as they take calculated risks in the process of pursuing their dreams. Mark contemplated this truth prior to climbing Makalu in 1995 and came face to face with it during the climb to the summit and during his arduous and heartbreaking descent to safety. Makalu is the fifth highest mountain in the world at 8463m, just 385m lower than the summit of Everest. When Mark returned from Makalu in June 1995 I remember meeting him in the Adelaide Botanical Gardens to hear about his experience. I hadn’t seen him for over three months and was excited to hear the story but also mindful that he had come face to face with a ‘dragon’ and needed an empathic ear to help unravel the knots he carried within his heart and mind. His story was inspiring, confronting, and as it turns out, a prophetic glimpse of what was to come for him on Mt Everest six years later. A year before the Everest climb I invited Mark to share the Makalu story with a group of leaders that I had been working with. The following summary of the Makalu story is based on a transcript of Mark’s words that were recorded during this presentation. Mark’s Makalu Story―Told by Mark Auricht The plan was for us to climb Makalu without supplementary oxygen and without the assistance of climbing Sherpas on the mountain. This was a minimalist and more purist approach but also more challenging compared to the other two teams (the French and Spanish Basque teams) who were on the mountain at the same time as us and had more significant Base Camp support. Prior to the trip I experienced a lot of doubt... I knew I was capable of getting to the top but wasn’t sure how things would pan out? A whole lot of factors have to come together to allow you the rare opportunity to stand on the summit of an 8000 metre peak. For a start there is a very narrow window of opportunity to climb at this altitude. There is a jet stream of wind that blows across Asia at about 8000 metres and above. The big planes flying across Asia get up into the jet stream which helps them to fly across the continent more efficiently. This jet stream blows at about 80-100knots and makes climbing very difficult and dangerous above 8000 metres. At this time of year however, in late April to early May, you’ll see plumes of snow being blown off the top of the mountain as the warm air of the monsoon arrives, forcing the jet stream off the mountain top and creating a window of opportunity where summiting is more possible. Then once the monsoon is in full swing the opportunity is lost. The exact timing and duration of this window is unpredictable but usually provides 2-3 weeks of optimal opportunities to reach the summit successfully. Many weeks of preparation and establishing camps at stages up the mountain to provide a launching point, need to be completed successfully to position climbers high up on the mountain, ready to go for the summit as soon as the jet stream is gone. So everything is geared around getting your body acclimatised properly and having the mountain kitted up with gear ready for summit day. We needed to be healthy, fit and ready when the favourable weather window opened to allow us our little piece of time on the top. We had seven climbers in our Australian Makalu Expedition to start with but eventually only two of us were in a position to try for the summit. You never know who is going to get sick, who will pull out or if indeed you or a member of your team will come back alive from an 8000m peak. We all knew the risks and were prepared to face them. Most expeditions will establish six staging points on Mt Makalu